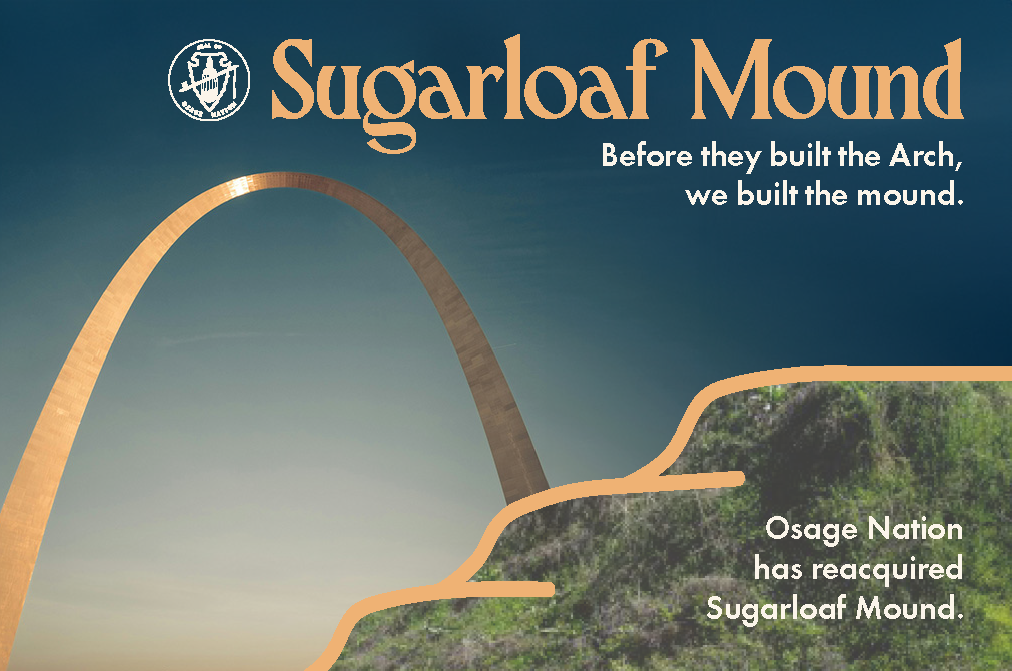

Sugarloaf Mound

Osage Nation reclaims Sugarloaf Mound

Osage Nation reclaims Sugarloaf Mound

Sugarloaf Mound

St. Louis’ Last Standing Mound

HISTORY

Excerpts from “Saving Sugarloaf Mound” by Andrew B. Weil and Dr. Andrea Hunter, in CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship, Volume 7 (1), 2010.

As the oldest human-made structure in St. Louis and the last Native American Mound in what was once known as "Mound City," Sugarloaf Mound links the present with the past. Sugarloaf is likely a Woodland period burial mound or a Mississippian platform mound, and dates to a time when the region was home to thriving and highly advanced Native American cultures long before the arrival of European and African people.

When the French began construction of what would become St. Louis in 1764, the future city contained possibly hundreds of mounds. While many were relatively small burial mounds situated on the bluffs overlooking navigable waterways, there was also a major Mississippian civic-ceremonial complex located just north of the Gateway Arch. The North St. Louis Mound Group included over 25 mounds systematically arranged around public plazas. This substantial site was presumably tied to two other nearby Mississippian centers: the little-known East St. Louis Mound Group and its famous relative, Cahokia (a UNESCO World Heritage Site).

By the late eighteenth century these Mississippian cities had been long abandoned. Yet French cartographers recorded the unusual earthen structures as prominent features on the landscape. The mounds also are visible in several early representations of the city, such as John Caspar Wild's 1840 lithograph of the city's north riverfront. By this time, however, Missouri's first governor, among others, used the mounds as platforms for their houses. A beer garden was placed on one and the city's first reservoir on another. By 1875, the mounds were nearly completely destroyed.

The lone survivor is Sugarloaf. Its location at the edge of a steep bluff several miles from downtown insulated Sugarloaf from industrial and developmental pressures that swept away the other mounds. Not altogether unscathed, in 1928, a house was erected on its top. The house on Sugarloaf was occupied continuously until 2008, when the property was offered for sale.

Over the years, ethnologists and historians have interpreted and published tribal oral histories pertaining to the migrations of the Osage and closely related tribes: the Kaw, Omaha, Ponca, and Quapaw. Together these four tribes, with the Osage, make up what is known as the Dhegiha Siouan language subgroup.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, ethnologist James Dorsey collected oral histories of migration stories from Dhegiha-speaking tribal members. Dorsey was told that in the distant past, all five Dhegiha tribes were once one nation that lived east of the Mississippi River in the vicinity of the Ohio River. The people migrated together, until they reached the Mississippi River, where the first segregation occurred. The people descending the river were called the Quapaw, meaning "the down-stream people." Those ascending were known as the Omaha, or "those going against the wind or current." The ancient Omaha, composed of the Omaha, Osage, Kaw, and Ponca, traveled up river until they reached the mouth of the Missouri and they dwelled near present-day St. Louis for many years. How long they stayed in the area as one tribe varied, with each present-day tribe venturing west and north at intervals. What would become the Omaha and Ponca tribes departed the Cahokia area first and then later the Kaw departed leaving only the ancestral Osage of the Dhegiha Siouan group in this core St. Louis area of the Mississippian domain. Approximately A.D. 1350, the ancestral Osage began their western movement into the oak-hickory forests of Missouri. Only when the Osage occupied southwest and south-central Missouri does the historic record of the tribe begin. Thus, for the Osage, the migration stories indicate that among the Dhegiha, the Osage inhabited the St. Louis region for the longest period of time.

From the 1920s onward, the archaeological record and identity of the Osage have intrigued scholars. As recently as 1993, Susan Vehik and Dale Henning (separately) reassessed the Dhegiha origins studies. They examined current archaeological data and scrutinized all lines of evidence to determine Dhegiha origins. Vehik reasoned that even given some differences between the Dhegiha tribes' migration stories, "all of the available oral histories from the Dhegihan Sioux center on the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri rivers." According to Vehik, a Dhegiha origin from the Ohio Valley accounts for the wide-ranging similarities among the Dhegiha tribes and also between the Dhegiha tribes and the Mississippi Valley Siouan, Algonkian, and even some of the southeastern groups. Henning came to a similar interpretation. He relied on the tribes' own migration legends, linguistic analyses, history, and ethnohistory, and concluded that an ancestral Dhegiha locus is most likely in the Ohio River Valley with the tribes migrating west of the Mississippi River and then splitting into their respective tribes.

In the past decade and a half, other anthropologists and archaeologists proposed a Dhegiha affiliation to the earthen mounds located in the St. Louis area. In many instances they specifically cited the Osage as the tribe with a strong association with the St. Louis/Cahokia Mississippian culture. Besides migration traditions, the evidence examined included: the use of mounds, house structure, village organization, war trophies, combat weaponry, subsistence practices, iconography (pottery, ceremonial objects, and rock art), religious practices, cosmology, and social structure-moiety systems with clans and bands.

The Osage people and their society governed a vast area of what is now Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas, and Oklahoma. The current Osage Nation Reservation is in northeastern Oklahoma, but it has been established that the ancestors of the Osage were among those who constructed the mounds in the St. Louis area, including Sugarloaf Mound and the complex at Cahokia. In a display of historic justice and bittersweet irony, the Osage Nation reclaimed Sugarloaf Mound by purchasing a significant portion of the property with assistance from the Osage Nation Historic Preservation Office and Principal Chief Jim Gray.

PURCHASE

In 2008, the house built on the summit of Sugarloaf Mound in 1928 was put up for sale by the owners. Almost immediately, the St. Louis community called for the preservation of the mound. After unsuccessful attempts to encourage the state of Missouri to buy the property, archaeologists contacted the descendants of the mound builders, the Osage.

Also concerned that any other new owners may tear down the mound as well as the old house, the Osage Nation stepped forward to preserve the sacred site. Principal Chief Jim Gray and THPO Dr. Andrea A. Hunter spearheaded efforts for education and community support for this important preservation opportunity. After 10-months of planning, organization, and negotiation, the Osage Nation moved forward to put Sugarloaf Mound back in native hands. In 2009, the Osage Nation finalized the purchase of the property. With that purchase, the Osage now own the summit of the mound, only 1/3 of the mound itself.

VISITS

Since 2009, the Osage Nation has worked towards obtaining the necessary funds to move forward with short-term and long-term preservation efforts for Sugarloaf Mound. The ONHPO installed security cameras at the mound to deter vandalism, purchased fencing to protect the site, and shifted the ornamental landscaping to a preservation and stabilization-based landscaping. As part of the annual Osage Heritage Sites Visits, the ONHPO regularly brings Osage members to Sugarloaf Mound to experience the sacred site and share the history of the mound.

PRESERVATION

In the summer of 2017, the ONHPO contracted a well-respected demolition company from St. Louis to assist in the removal of the 1920s house on the summit of Sugarloaf Mound. Staff members of the Osage Nation Historic Preservation Office monitored the deconstruction of the house to ensure a successful outcome. Although some of the interior-facing retaining walls had to remain to ensure internal mound stability, the majority of the old house was eliminated from the mound profile. The removal of the house was a major step in the long-term preservation and management goals of the site, which will culminate in the future establishment of an Osage-run interpretation center.

REFERENCES

For the complete report regarding Sugarloaf Mound and the planned preservation efforts, refer to “Saving Sugarloaf Mound” by Dr. Andrea Hunter and Andrew Weil, in CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship, Volume 7 (1), 2010.

WAYS TO SUPPORT

Purchase Merchandise

PURCHASE THE OSAGE ANCESTRAL TERRITORY MAP

Indirect Donations

Your purchases on Amazon.com can support the Osage Nation Foundation by using smile.amazon.com. To ensure the Osage Nation Foundation receives these funds, go to your Amazon Smile account and select Osage Nation Foundation.

Donate Directly

Please send donation checks to the Osage Foundation with "SUGARLOAF MOUND FUND" in the memo line.

Checks can be mailed to:

SUGARLOAF MOUND FUND

C/O Osage Nation Foundation

P.O. Box 92777

Southlake, TX 76092

OR

Visit the Osage Foundation Website and use the donate now button to donate through PayPal.

Please add “SUGARLOAF MOUND FUND” to the special note field when donating through PayPal.

Other ways to Give

Visit the Osage Nation Foundation website for other ways to give.

If you have donation questions or would like more information, please email @email.

Physical Address

Historic Preservation Office

100 W. Main

Pawhuska, OK 74056

Office Main Phone

918-287-5328

Office Fax Number

918-287-5376

Email

@email